Thomas Drew (1810-Aft. 1870)

Born: 1810, County Meath, Ireland.

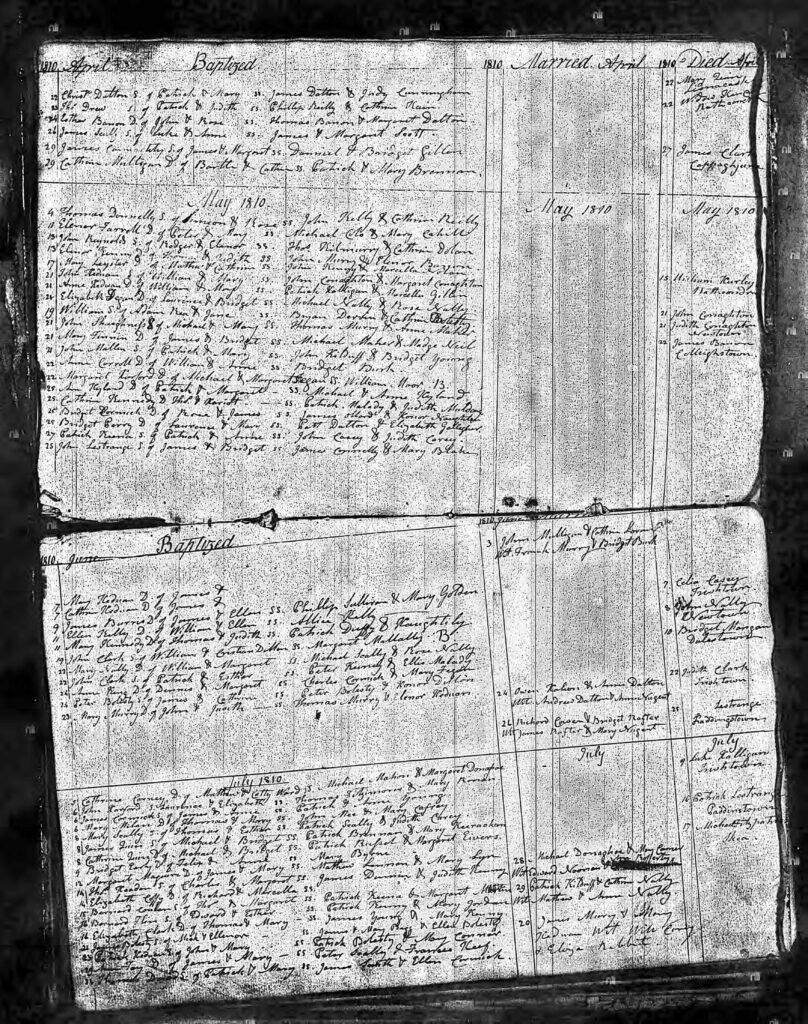

Baptised: 23 April 1810 to Patrick and Judith Drew, Milltown, County Meath, Ireland.

Married: 24 August, 1832 to Margaret Fitzsimmons, Gillingham, Kent, England.

Died: After 1870, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

Children: Maria Drew (1835-), James Henry Thomas Drew (1837-1843), Alfred Rochford Drew (1838-1881), Francis Henry Drew (1840-1891), Frederick Drew (1842-), Frederic Augustus Drew (1843-), Henry Thomas Drew (1844-1893), Rosalia (Rose) Maria Drew (1846-1875), Lydia Clara Mary Drew (1847-), Remigius Edward Drew (1850-1851), Ann Margaret Drew (1852-), John Thomas Drew (1857-1911).

Researched by his Great-Great-Great-Great Granddaughter, Kate (2026). Email with any enquiries.

Early Life

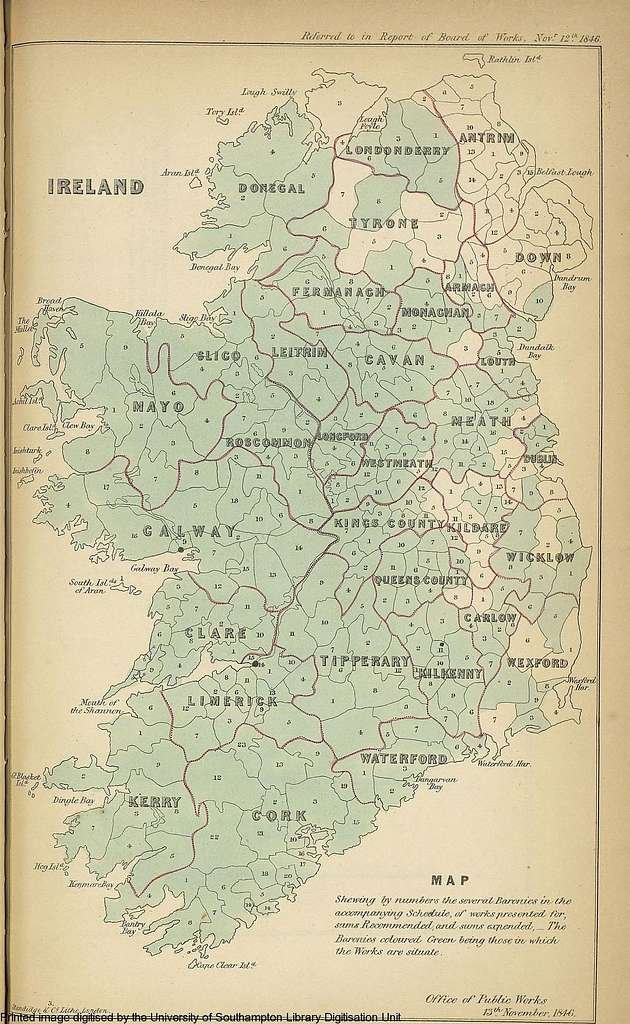

While there are some gaps in our knowledge of his early life, we know that Thomas Drew was baptised in Milltown, County Meath, Ireland on the 23rd April 1810 to Patrick and Judith Drew. The baptism record of his brother – Patrick Drew (Jnr) – is recorded 20km away in Rathkenny, County Meath, leading us to think they were both born and raised in this area.

County Meath is in the Eastern/Midland region of Ireland, bordered by County Dublin (and the capital city, Dublin) to the Southeast. The county is colloquially known by the nickname “The Royal County“, owing to its history as the seat of the High King of Ireland.

The earliest known evidence of human settlement in the county have been dated to 9,500 BC. Due to a lack of extensive written historical records prior to the 5th century AD, the early history of Meath is heavily mythologised, but accounts of the arrival of Saint Patrick (in the 5th century AD) and Christianity to Ireland are centred on Meath and its legendary High Kings. 1000 years later, after declaring himself the head of the Church of England, Henry VIII proclaimed the formation of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542, with himself as its monarch.

The Reformation that then occurred lead to ongoing division between Protestants and Catholics that persists to this day. From Thomas Drew’s baptism records, we can see that the family were Irish Catholic. The long-oppressed Catholic population in Ireland were rarely land-owners or members of the gentry. There were limits on education for Catholics, despite multiple rebellions, restricting their opportunities.

With the creation of the The Acts of Union 1800, Ireland was made part of the United Kingdom. A decade later Thomas was born into a land that, at the end of The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), was struggling economically. Poverty was widespread throughout Ireland in the early 1800s. Landless labourers (cottiers) comprised the single most common profession at a time when 40% of Irish houses “were one room mud cabins“.

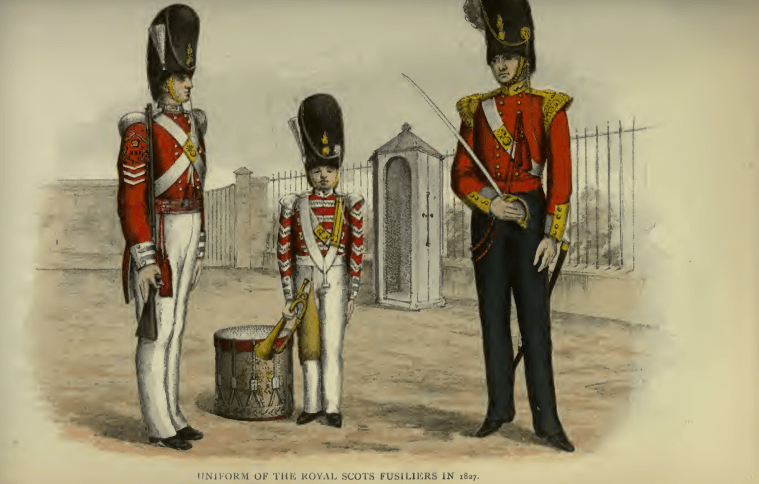

Large numbers of Irish soldiers (who comprised as much as 25% of the entire British military during the war) were made redundant after the Napoleonic Wars, yet, despite this – Thomas enlisted in 1826 (at age 16) into the 21st Royal North British Fusiliers [later Royal Scots Fusiliers]. His brother Patrick enlisted with him. Together, their duties would take them from rural Ireland to the farthest corner of the British Empire.

A famous ‘air’ (song) “Planxty Drew“, composed by blind Irish harper Turlough O’Carolan (1670-1738), is thought to have been written for one of the Drews of Drewstown House, County Meath, near Athboy and close to the border with Westmeath. The family scion was Francis Drew, a Captain in Queen Elizabeth’s army in 1598. (TTA) This indicates that Thomas and Patrick Drew were likely one of many generations of Drews in County Meath that served in the military.

“In 1815, when war between Britain and France ended, the aftershock was felt far away in Sydney. As soldiers headed home from the battlefields – to British towns and cities already racked with hardship and poverty – a rapid spike in social unrest, unemployment and, in turn, rising crime pushed courts and prisons to the brink. To relieve the pressure on lockups and jails, and serve as a dire warning to would-be criminals, it was decided to increase the flow of convict workers to the distant settlements of New South Wales.”

From Ireland to Australia

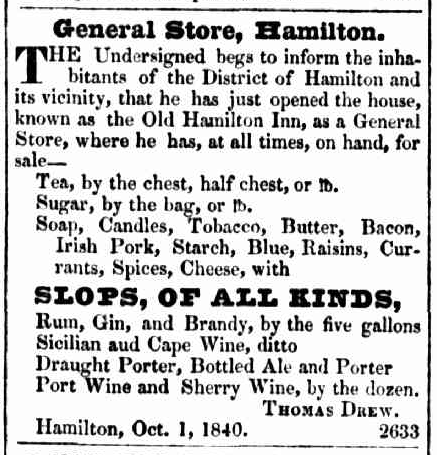

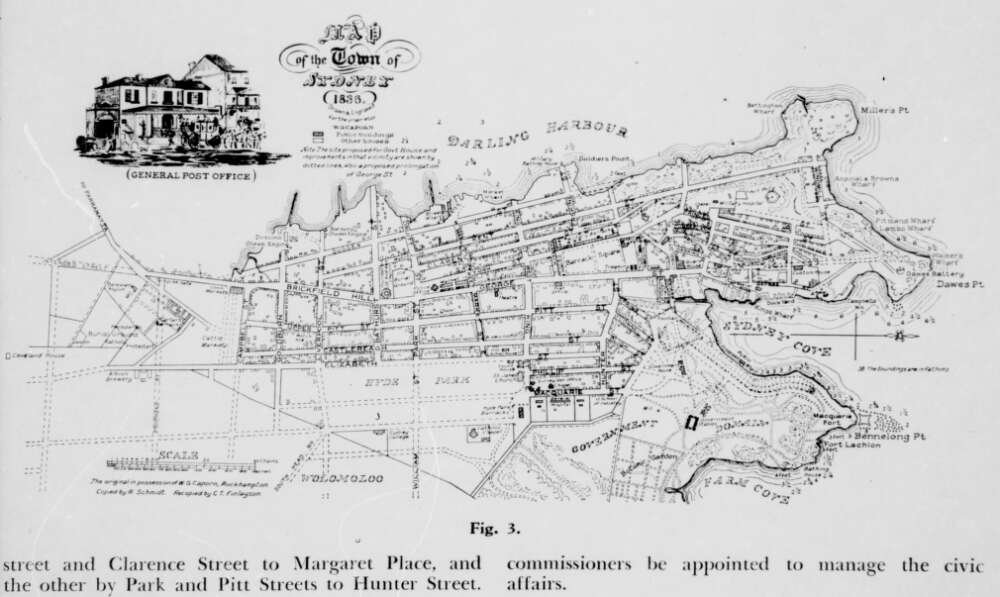

The 21st Royal North British Fusiliers marched in September 1831 for Dublin, then embarked for England in October. In 1832, they moved to Chatham (Clark 1885). It is here – in nearby Gillingham, Kent – that Thomas marries Englishwoman Margaret Fitsimmons on 24th August, 1832 (England, Select Marriages, 1538-1973, FHL Film #1042493, Ref. ID: 33). Less than a year later, the regiment “embarked by detachments in charge of convicts for New South Wales, Australia, and Van Dieman’s Land (now the island of Tasmania), the last detachment arriving at Hobart Town in 1833.” (Clark 1885, p. 42).

Thomas (accompanied by Margaret) departed Dublin aboard the Royal Admiral convict ship bound for Sydney, Australia as one of the Fusilier escorts for 220 male convicts, arriving on 13th November, 1833.

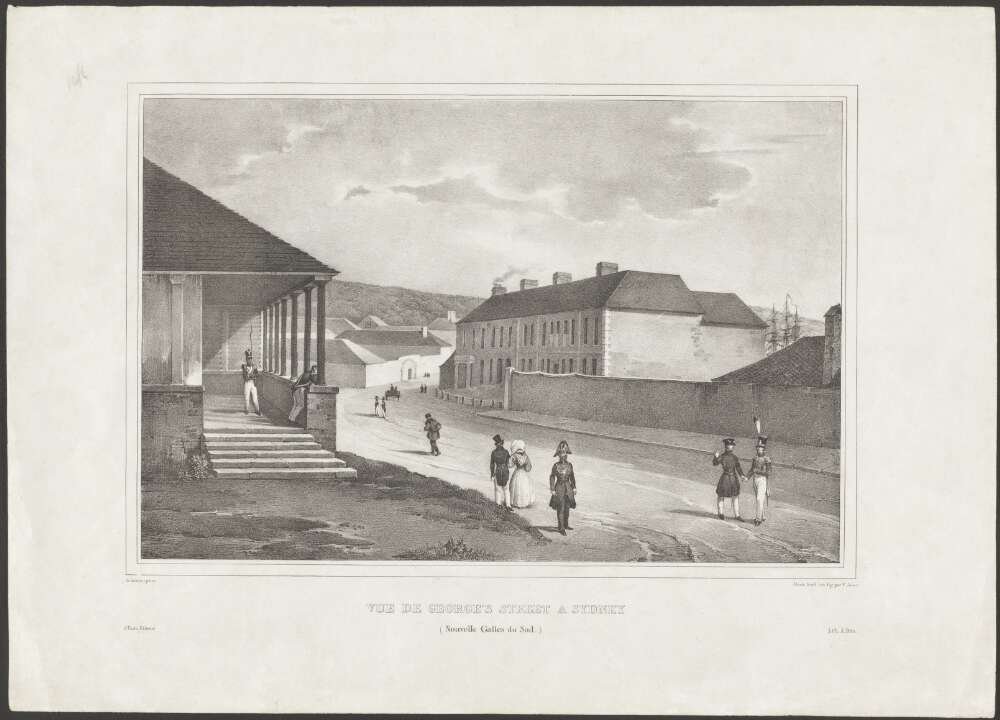

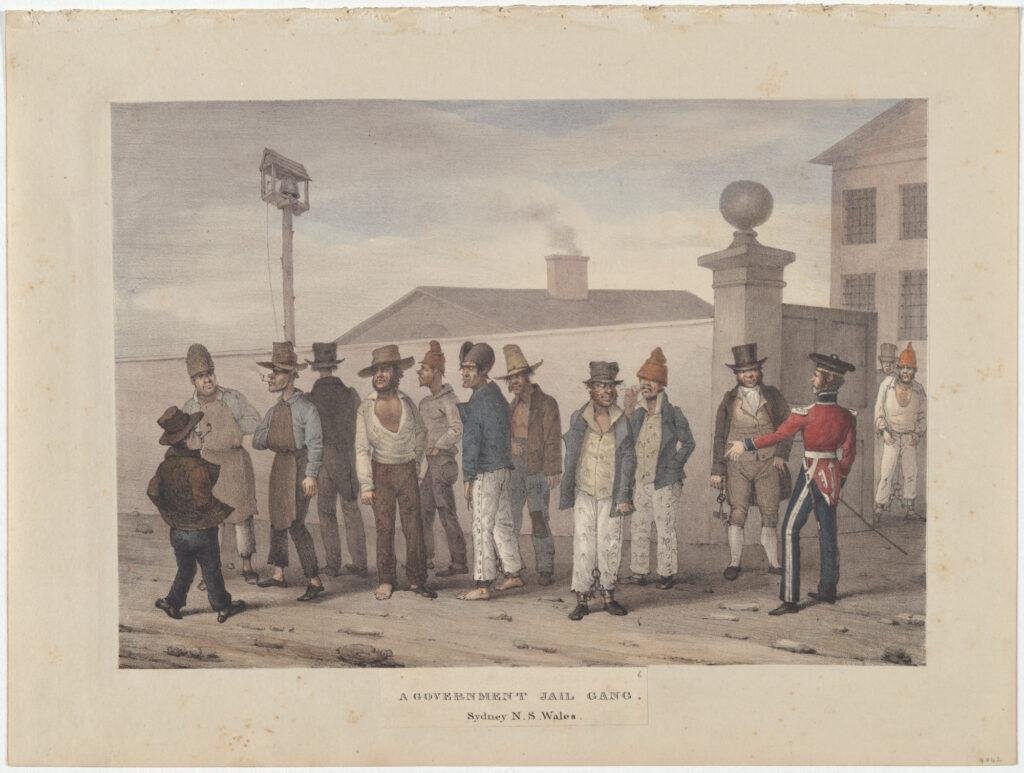

“The male prisoners by the Lord Lyndoch and the Royal Admiral, were landed at the usual place in The Domain, on Monday morning last, and were marched up to Hyde Park Barrack previously to being assigned to masters.” (NLA)

Convicts were brought to Australia under an…

“…assignment system… [which] from 1826 onwards, were to equip farmers with cheap convict labour, to disperse convicts away from towns (and other convicts) and to keep an eye on each worker’s whereabouts and treatment… At the heart of this system was the administrative hub of the Hyde Park Barracks, coordinating the labour, location, fortune or fate of convicts across the broadening reach of settlement.” (Museums of History New South Wales)

“The convicts living at the barracks were controlled by a delicate balance of freedom and restraint: they were prisoners, but the barracks was not a prison. Convicts arriving in Sydney Cove were marched up the hill to the barracks. After being mustered in the yard, some were quickly assigned to work for colonists, while those with useful trades were kept in government service and lived at the barracks. These convicts were required to work for the government during the week but were allowed to work for their own benefit on Saturdays.

In 1830 a Court of General Sessions was established in the buildings along the northern perimeter of the site, turning the complex into a busy administrative hub for the colonial convict system. Here convicts from around the colony faced trial for secondary offences and disputes between convicts and employers were settled. Fortunate convicts were presented with pardons and tickets of leave, but disobedience and small misdemeanors were punished with solitary confinement or flogging on site. More serious crimes meant a longer sentence, months of work in a chain gang, or banishment to the dreaded penal stations of Norfolk Island or Port Arthur.” (MHNSW)

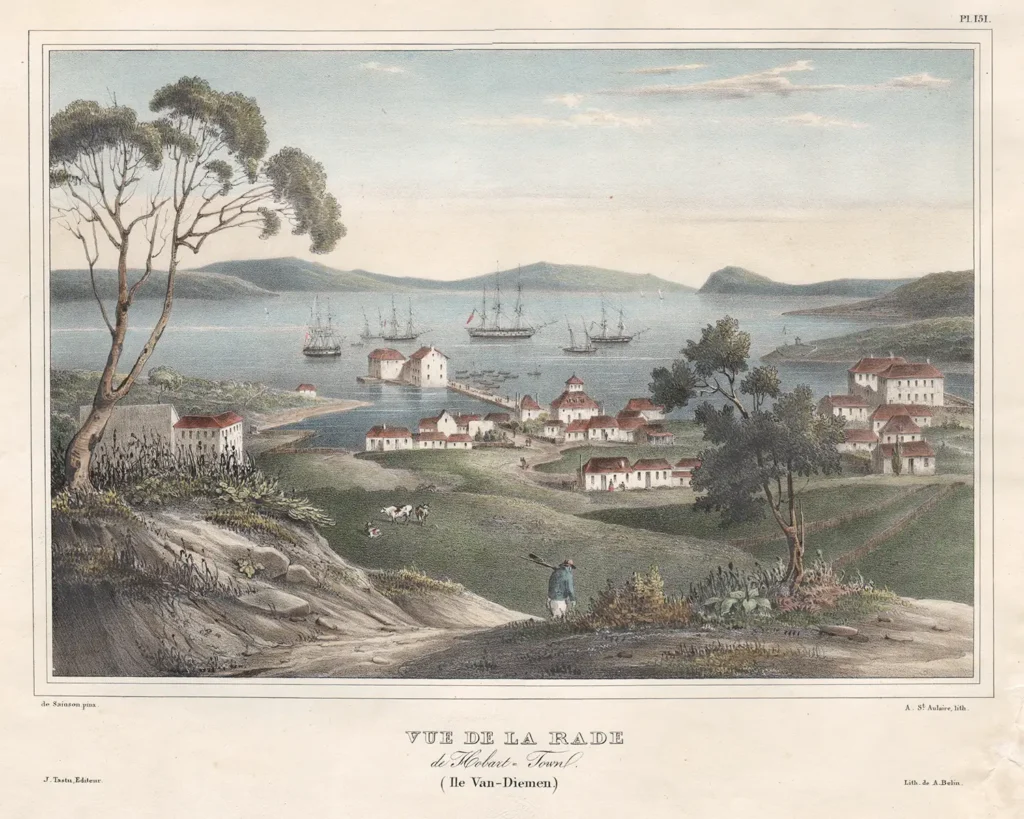

Less than a month later, Thomas and Margaret boarded the Lord Lyndoch to Hobart Town, arriving on 10th December, 1833.

Arrived on Tuesday the 10th instant, the ship Lord Lyndoch, 638 tons, Capt. Johnston – in ballast – with Colonel Leahy, Capt. Wrixin, Lieuts. Larnotte, Ainslie and Mundy, Quartermaster Fairgraves, and 149 rank and file of the 21st; also Capt. Mundalkin of the 5th regt., Dr Stewart, R.N. Mrs Wrixin and family, Mrs. Fairgraves, 25 women and 27 children. (NLA)

Hobart Town (henceforth referred to as ‘Hobart’), first colonised by the British in 1803, was “[a] busy port and the preponderence of convicts in the population meant that Hobart was still ‘wild and unruly’ with a high crime rate.” By 1830. the population was approximately 6000.

“Convicts, numbering more than 65,000, first set foot in Tasmania at Old Wharf before marching in chains to the barracks. By 1830 the new, deeper harbour at Salamanca Place was bustling with whaling ships, sailors, smugglers and traders. Captain James Kelly, one of Hobart’s most colourful figures, built the stone steps that still link Battery Point to the waterfront. Kelly’s Steps remain a daily pathway for locals, a reminder of those raucous, formative years… Hobart’s waterfront grew into one of the world’s busiest whaling ports. Convicts disembarked at Old Wharf, sailors brawled in laneways, and merchants amassed fortunes. In the 1830s, New Wharf was built at Salamanca Place, lined with warehouses of convict-quarried sandstone.” (SAC)

While we don’t know much about Thomas and Margaret’s early life in Hobart, we know that they had begun to have the first few of their 12(!) children, Maria (1835-), James Henry Thomas (1837-1843), and Alfred Rochford (1838-1881). Having been accompanied by his wife (and now growing family), it is likely that Thomas’ duties during this time allowed him to remain local to the area, although this was not always the case for his fellow soldiers. “[F]rom 1834 to 1838, the Fusiliers were employed throughout Tasmania… on detachment duty in charge of various convict stations, and parties on public works (Clark 1885, p. 43).”